Three Psilos is proud to introduce Ecology Dogs; highly trained canine experts specializing in Applied Ecology.

Ecology Dogs support ecologists and environmental professionals by performing tasks that require a heightened sense of smell, acute hearing, and the ability to navigate diverse terrains. Much like other working dogs, Ecology Dogs are trained to assist in various ecological and conservation efforts, utilizing their natural instincts and specialized training to contribute to the preservation and restoration of natural environments. Consider them Specialists in Canine-Assisted Ecology.

Role and Functions

Ecology Dogs perform a wide range of tasks in applied ecology, including but not limited to:

1. Tracking and Searching:

– Mammals: Identifying and tracking routes of species such as black bears and Florida panthers, including locating birthing sites or dens.

– Birds: Locating injured, orphaned, or nesting birds to assist with rehabilitation or conservation efforts.

– Reptiles: Detecting and tracking species such as gopher tortoises, monitoring their burrows, and assisting in relocation efforts.

– Fish: Identifying signs of fish activity in streams or ponds, especially in monitoring efforts for endangered aquatic species.

2. Flora and Mycology:

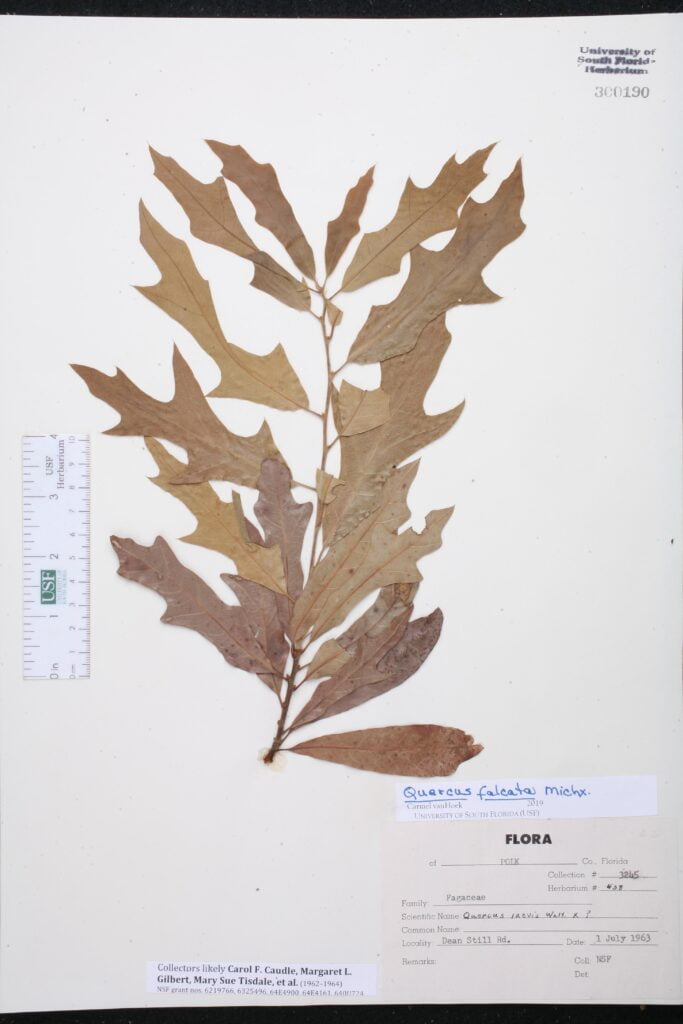

– Plant Species: Searching for specific plant species like Ghost Pipe or other rare flora to create or enhance mycological networks necessary for the growth of endangered vascular plants.

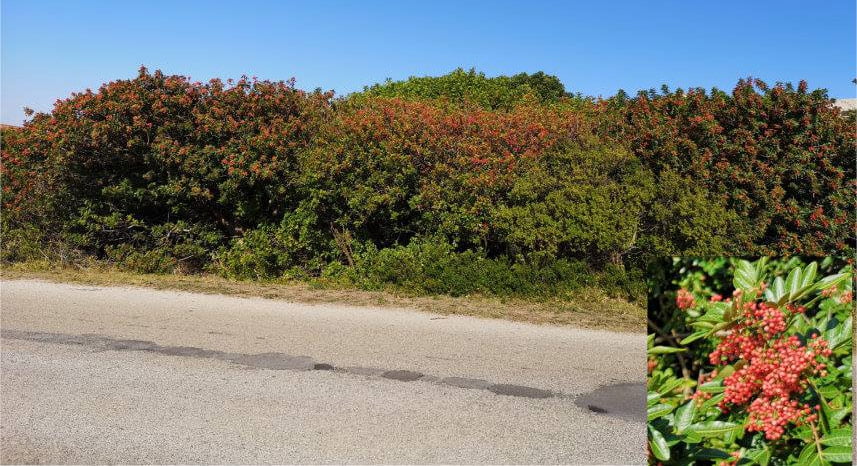

– Invasive Species: Locating and helping remove non-native invasive plant species such as Brazilian peppertree or cogongrass, even assisting in physically tearing out seedlings.

3. Wildlife Management and Conservation:

– Scat Detection: Identifying and analyzing scat to track wildlife activity and health in a specific area.

– Herding: Assisting in herding or removing invasive species or livestock that threaten local ecosystems.

– Search and Rescue: Participating in search and rescue missions in wildland firefighting, forestry, or during natural disasters, aiding in locating lost or injured individuals.

4. Rehabilitation Assistance:

– Orphaned Wildlife: Assisting ecologists in finding and caring for orphaned wildlife, playing a role in the rehabilitation and eventual release of these animals back into the wild.

Training and Psychology

Ecology Dogs are trained using principles from the Dog Psychology framework developed by Cesar Millan, which emphasizes achieving “calm surrender” and giving dogs meaningful jobs to provide them with fulfillment. This approach ensures that Ecology Dogs are not only effective in their roles but also well-balanced and content, leading to better performance and a stronger bond with their human handlers.

Lexicon Development

1. Ecology Dog: A canine technician specialized in applied ecology, trained to assist ecologists with various tasks related to conservation, wildlife management, and environmental restoration.

2. Canine Technician: A highly skilled dog trained in specific tasks related to a particular field of work, such as ecology, search and rescue, or detection.

3. Flora Finder: An Ecology Dog trained to locate specific plant species, especially rare or endangered flora, and assist in conservation efforts.

4. Fauna Tracker: An Ecology Dog skilled in tracking and identifying the routes, dens, or nesting sites of mammals, birds, reptiles, or amphibians.

5. Scat Scout: An Ecology Dog trained to detect and identify animal scat, aiding in wildlife tracking, health monitoring, and ecological studies.

6. Invasive Herding: The act of an Ecology Dog herding or guiding non-native invasive species for removal, supporting efforts to restore native habitats.

7. Mycology Assistant: An Ecology Dog specialized in finding specific fungi or mushroom species, crucial for creating the appropriate mycological networks for plant conservation.

8. Wildlife Rescuer: An Ecology Dog involved in the search, rescue, and rehabilitation of injured or orphaned wildlife, contributing to their recovery and reintroduction into the wild.

9. Ecologist’s Companion: A term that highlights the close working relationship between the Ecology Dog and the ecologist, underscoring the mutual trust and collaboration essential for their shared mission.

10. Nose for Nature: A colloquial phrase emphasizing the Ecology Dog’s superior olfactory abilities, making them indispensable in tasks requiring scent detection.

Non-Fruiting Brazilian Peppertree – Cut & Treat (per 12 in. of height)

Treatment for one Brazilian Peppertree, per foot of its height. Includes cutting of all branches at the base, herbicide treatment of the resulting stump, and preparation for removal to landfill. Does not include removal of waste to landfill.

Add the quantity of feet in height of your Brazilian Peppertree to your cart, e.g. a 10 foot tall tree needs a quantify of 10 added to your cart.

Encouragement for Integration

Integrating Ecology Dogs into environmental and conservation efforts offers numerous benefits, including increased efficiency in tracking and monitoring, improved success in locating and managing both flora and fauna, and enhanced support in wildlife rehabilitation. By embracing the use of Ecology Dogs, ecologists can leverage the unique abilities of these highly trained canines to advance ecological research and restoration efforts, while providing the dogs with meaningful and fulfilling work that aligns with their natural instincts.

Ecology Dogs represent a powerful synergy between human and canine, where each species brings its strengths to bear on the critical tasks of environmental stewardship and conservation.